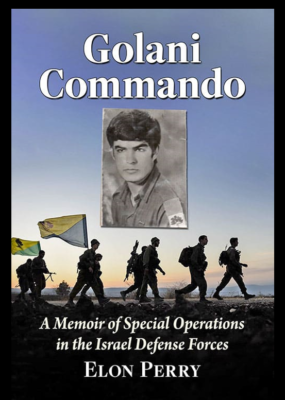

Amazon UK has copies on its site. See: Golani Commando: A Memoir of Special Operations in the Israel Defense Forces. For a signed copy please contact me at send890@gmail.com and I will post it to you.

A revealing look into how someone so young becomes a warrior and Patriot. Elon Perry joined the Israel Defense Forces –one of many young Israelis who reluctantly entered military service in an adult war–and was enrolled in an elite commando unit of the decorated Golani Brigade. Covering 28 years of compulsory reserve duty through the Lebanon War, antiterrorism operations and the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict, his frank, reflective memoir describes the grueling Golani training regime–described by many as Mission Impossible–and contrasts the exhilaration of high-risk operations in enemy territory with a disdain for war, its moral dilemmas and its victories. Fantastic read!

Professor Steven Greenblatt, Harvard University

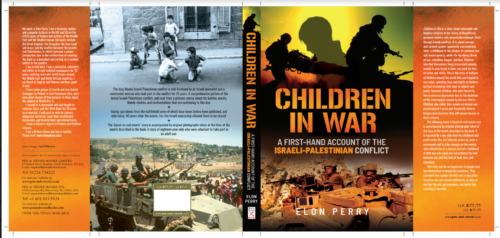

My second book:

Children in war

A story based on real events about vulnerable, helpless children at the mercy of bloodthirsty pompous leaders who constantly endanger them through bloody conflicts. It is about harsh childhood in the shadow of constant war and severe poverty due to the depletion of the state budget caused by the war efforts. Children who could not comprehend the link between war and the lack of food, toys, and chocolate. Scarred children who suffer from severe emotional and psychological trauma and constantly witness images and situations that will remain in their memory forever.

To order directly from the publisher please use this link:

https://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/Children-in-War-Hardback/p/49850

A chapter from the book:

When I look back on my childhood, I wonder how I survived at all. The oppressive hunger and the unbearable poverty. No pocket money, no birthday celebration, no chocolate, and no bedtime story. No sweet dreams and no laughter. Above all, the fear of the wail of the siren and the incessant war that forced me to spend long days and nights in damp and malodorous shelters.

To ease the constant anxieties and nightmares, our grandmother would put salt under our pillow and assure us that God was watching over us and would protect us if we prayed three times a day and believed in Him wholeheartedly. At school, which was nothing more than three long brown wooden huts, the atmosphere was melancholic and murky. The violent and bullying teachers were convinced that beating a child who dared to ask a lot of questions was the perfect way to turn him into a smart academic. One of them, the flame-haired Mr Meir, beat me for naively correcting him when he got the date wrong of the storming of the Bastille. Another bullying teacher was Sophia the Fat, the elderly spinster who used to take out her frustration and bitterness on us for not being able to get herself a husband.

Out on the streets, there was the daily danger of getting caught in the net of the criminal gang that I hung around with and used to commit petty thefts with. The leader, who was much older than us, noticed my creative mindset and started enticing me with pocket money here and there to lure me into the gang. He even surprised me with a brand-new pair of sneakers so that I would feel indebted to him and the gang and immerse myself in their criminal activities.

My troubles began the night I was born. Instead of joy and celebration, my frightened and trembling mother, who still hadn’t recovered from the terrible pain in her bleeding groin, had to carry me all the way to the shelter because that very night the Egyptian army decided to bomb us. As if they couldn’t postpone their shelling for a few days, at least until I had taken nutrition from my mother’s breasts, or at least until I had opened my eyes to see where they were taking me in such a panic. By the time I was three years old, I had become an expert at running to the shelter.

On a fiercely stormy night in the winter of 1962, with successive bursts of thunder and flashes of lightning getting ever closer, my mother came to the room where each night my two brothers and I would be huddled in the large double bed shared by the three of us. My mother wished to make sure that the window in our room was tightly closed, and that none of us would be alarmed by the deafening noise of the thunder. As she entered the room, she was horrified to discover that our bed was empty. She was overcome by panic and immediately woke up my father who was fast asleep. ‘The children are gone!’ she screamed and started wailing in fear. My father jumped from the bed and searched the entire house while reassuring my mother, who continued to cry and whimper. Only after many minutes of panic, did they find out what had happened to their small children. It turned out that their usually disciplined children, who had been woken up by the thunder, had jumped out of their beds, and without waiting for instruction, raced down to the bomb shelter just a few metres down the road, believing the thunderous noise was yet another bombardment from Gaza. To us as children, our run down to the bomb shelter was no more than our daily routine, and we were sure our reaction was a necessary and normal act. To the adults around us, it was a disturbing incident that symbolized the horrific reality we were living in, the madness of growing up under the shadow of war.

Sitting in an underground ditch or shelter became part of our lives. I became accustomed to spending so much time in shelters that each time we ran towards one, I found myself worrying more about the discomfort of sitting for several hours in the damp bunker than about the shelling outside. I was worried about inhaling the breath of others, especially those who had been eating garlic that day, or the smell of baby vomit tinged with the odor of piss wafting in from outside. This in addition to a constant and unbearably strong stench of sweat from those who hadn’t showered in days due to the lack of hot water. The only times I enjoyed sitting in a crowded shelter was if I was crammed next to a sweetly perfumed woman or one of the prettiest girls in town.

But sometimes the run to the shelter was fun for us, a kind of competition to see who would get there first. However, for the adults, it was a burden. My mother, heavy with the next child in her belly, would heave herself from the bed, struggling to make her way to the shelter while panting and muttering indistinct words. My mother was always pregnant, every year. I don’t remember a day without seeing her body bloated. My parents, like most of the respected townspeople, were pious souls, devoutly loyal to God and tradition, obedient to the divine imperative to breed as many children as possible. In return, God, who was just around the corner, would grant them a life of peace and tranquillity as a reward for their faithfulness. In the meantime, until they were redeemed, they were required to continue showing their loyalty and faith in the almighty God, even if it was laced with great suffering.

Yearning for fresh and pleasant air caused bitter arguments between the adults in the shelter, about whether to leave the door and the steel windows open or not. The fear of hearing the bombs landing outside caused some people to panic and insist on closing them, despite the difficulties in breathing. But fresh air was not the only problem. The whole damn shelter was dilapidated to the point where it seemed about to collapse at any moment. The cracked outside walls were colourful with promising graffitied messages but on the inside, these walls were damp and dingy, never seeing the sun’s rays even though the sunlight was gleaming brightly outside. In the winter, lines of leaking water would be seen careering down the walls from the ceiling. None of the adults could do anything about the lurking danger from the damp walls that created a cacophony of hacking coughs and bronchial rattles among us all. They all seemed to be busy surviving hour by hour, helpless, torn apart by their nightmares and constant existential anxieties, and above all, the feeling of personal failure in not being able to provide for their families.

I was born under an ongoing war between two stubborn nations: the Arabs who felt dispossessed of their land, and the Jews who felt a strong need for a refuge where they would be safe from pogroms, persecution, and another Holocaust. Each of them claims ownership of a holy land, a land whose rivers are filled with blood due to their leaders’ fanatical belief that they are fulfilling God’s wishes. An imaginary god who doesn’t bother to intervene simply because he doesn’t exist.

As a result, I, as well as other children, both Palestinians and Israelis, did not get to experience a calm and normal childhood, nor a fun-filled youth spent at parties and with the enjoyment of the first kiss, as a happy-go-lucky Swiss boy would. I did not know what a bathtub looked like, and our lavatorial needs were serviced by an improvised WC situated behind the house. Once a week, a truck with a large black container and suction pipes would arrive and pump out everything that had accumulated in the pit below the makeshift toilet. My birthday was never celebrated, and a weekly visit to a cinema was nothing but a wishful illusion. I only got to know what the world looked like outside Israel through a small black and white TV my father had bought with what he had saved by making a little extra income from doing small repairs in the homes of the local people.

I felt exposed and vulnerable, helpless, facing a mighty force called war that was stronger than me. An existential threat that as a child, I did not have the strength to deal with. Instead of playing football in the schoolyard, or fooling around in the local playground with other children, I was forced to seek refuge inside oppressive bomb shelters from the wars imposed on us by our leaders.

My life was miserable only because of religion and God, the mystical nonsense that causes only bloodshed and grief. The wars over Jerusalem and the Holy Land have all revolved around one idea – religion. Empires throughout history conquered the Holy Land in bloody and brutal battles, convinced that God Himself lived there, hidden in the seams of the cracking walls of Jerusalem. The conflict between the Palestinians and the Israelis is not over valuable oil or diamond mines, but simply over the Holy Land and Jerusalem. And in the midst of it all, children are the victims. Children who did not choose to be born. Children who pay a heavy price for the madness of the adults. I was one of those. I felt like a victim of those rotten and nonsensical wars over the holy land and religion that serious people called politicians took very seriously. Wars, decreed by men dressed in suits and ties, are those who speak nicely in front of a microphone or camera and can lie without batting an eyelid. Those with bloated egos and morbid motivation are driven around in black armoured cars. Accompanied by guards and helpers and advisors who are constantly by their side, straightening their ties, and whispering in their ear, maintaining a serious look as if they are telling them something crucial, but in fact, reminding them of the name of the person whose hand they are about to shake. I was condemned to spend my childhood and youth under never-ending war just because of their personal ambitions; a long bloody conflict that ruined the lives of millions of Israelis and Palestinians, Muslims and Jews, who share the same biblical ancestor.

Millions of children around the world who live out their childhoods under the terrifying threat of war, finding themselves spending days and nights in shelters, living in constant anxiety, unable to play freely in their own yard for fear of sirens and shells. Vulnerable, helpless children at the mercy of their bloodthirsty and arrogant leaders. Children in war are the most endangered species in the world. They are trapped in war zones instead of enjoying their days in parks and schools. They suffer from severe emotional and psychological trauma and constantly witness images and situations that will remain in their memory forever. I was one of them. A child who was trapped in relentless conflicts in the Middle East over the Holy Land and religion – nonsense that serious people labelled politicians took very seriously. As a result, I was condemned to a childhood in the shadow of constant war, severe poverty, relentless danger, and fear. An oppressive childhood caused by continuous days of hunger and lack of clothing, footwear, toys, pocket money, gifts, or even birthday celebrations. This is in addition to being one of nine children huddled in two rooms with no privacy and minimal furniture.

I was born and raised under an ongoing war between two stubborn nations, each of which claims ownership of a tiny land whose rivers overflow with blood due to their belief. The Arabs felt dispossessed of their land, and the Jews felt a strong need for a refuge where they would be safe from pogroms, persecution, and another Holocaust. But as a child, I couldn’t understand this grown-up business. All I wanted was to play football in the yard and dream about finding myself locked inside a chocolate factory. I wanted to play games, swing on a swing, bump up and down on a see-saw, listen to music from an old tape recorder, and if lucky, enjoy a first kiss with a girl. I just wished wanted to live a normal life. However, the politicians decided otherwise and created a prolonged and bloody war, forcing me to spend my entire childhood in bomb shelters, living in perpetual anxiety and seeing a world only beyond the heavy metal door of the shelter.

Because of the personal ambitions of these politicians, thousands of children, both Palestinians and Israelis, were condemned to spend their childhood and youth under never-ending war. A long bloody conflict that ruined the lives of millions of Muslims and Jews who share the same biblical ancestor. Ordinary people whose wish was to live side by side in peace, but who are in reality smacked in the face by the behaviour of their leaders. Pompous men, described as leaders, smartly dressed in suits and ties and speaking nicely in front of a microphone or camera, experts in lying without batting an eyelid. Condemning their citizens to a life of fear and hardship, spending most of their life in severe poverty and deprivation, due to a situation of incessant war, which sucks up a nation’s budget to the point of starvation.

The difficulties I experienced in my childhood have followed me throughout the rest of my life and taught me how to make do with little, to appreciate everything, and to live modestly. I learned that I could survive any bleak times and any conditions. This was severely put to the test during my army service in the commando unit. My willpower forged me and gave me hope, and the possibility to dream and plan a promising and successful future instead of sinking into depression and giving up. Despite the inferno I went through, I did not choose the easy way out by turning to drugs and alcohol, but succeeded in graduating from university with two degrees, working as a journalist and lecturer, and receiving commendations and appreciation for inspiring thousands of others. As a poor hungry child shrouded in anxiety, I never dreamed that I would have a future. I was sure I would be a bum, a criminal, or a drug user, due to the daily danger of getting caught up in the web of a criminal gang that I hung around with and used to commit petty thefts with, and the constant temptations that were too much for my empty pockets. I never dreamt I would be a brave commando fighter in the best army in the world and perform the impossible.

A taste from the book – Golani Commando

A memoir of a commando fighter in the Israel Defense Forces

This is the story of a young man who was reluctant to take part in a long-lasting and bloody conflict. Because of personal motivation, due to a war of sheer survival that I happened to be born into, I chose to perform my military service in a commando unit to defend my beloved country, but I also wished to revenge the enemy that had ruined my childhood. I was born into war. I grew up on wars, bombing and shelters. Fears and nightmares were part of my childhood. Even in the playground, I could not really enjoy our childhood games because I kept expecting to hear the feared siren. The siren that would take us to the shelter for a few hours, and sometimes even for a few nights. Anxiety and fear surrounded me throughout my childhood and youth. I learnt that serving in a commando unit allows very close contact with the enemy. Thus, after passing many tests and overcoming difficult challenges, I was accepted and joined the Sayeret Golani commando unit. I served 3 years, during which time I saw death more often than the breakfasts I ate. They were years in which we did the impossible, the like of which was only seen in James Bond movies. I then served another 25 years in the army reserve service, where I was involved in many dangerous activities, and daring raids into Lebanon, in pursuit of wanted terrorists.

In the book, I describe my personal combat experience and the many daring operations my unit undertook in enemy territory, including those carried out in cooperation with the Mossad and other Israeli intelligence services. These were complex operations during which we underwent great risk and fear of death. Many of these dangerous and awe-inspiring activities and operations were accomplished using sophisticated techniques, and by employing imagination, creativity and clever use of deception. I will describe operations and raids on well-fortified terrorist strongholds to which we were sent, despite their slim chances of succeeding, and where the intolerable conditions gave justifiable feelings of fear and uncertainty. Sometimes these involved face-to-face and short-range combat, where the individual’s qualities and skills were the key to success. I also relate some of the methods used by the Israeli intelligence services, with which my unit participated in several raids and operations in Lebanon and Gaza, as well as in the West Bank. I reveal some daring, almost ‘suicidal’ operations which have never before been published, and only today, 30 years after the events, has the Israeli censorship allowed them to be shared. Some of these have gone on to inspire books and movies. In some of these operations I participated with the undercover ‘Mista’arvim’ unit in the war against terrorists. (A taste of this was seen in the popular Netflix series Fauda). In one of these operations, I came very close to death, but was saved by an unexpected source: one of the locals, a Palestinian resident of Gaza, with whom I am still in touch. This man was forced to flee Gaza and was granted asylum in the United States.

The Mista’arvim are trained commandos who operate undercover by posing as Arabs, both in their appearance and by speaking fluent Arabic. They assimilate among the local Arab population to capture wanted terrorists, gather information and help other combat units like us when fighting. While assimilating among the local Arab population, the Mista’arvim are commonly tasked with performing intelligence gathering, law enforcement, hostage rescue and counter-terrorism, and to use disguise and surprise as their main weapons to accomplish their missions. In one of these operations, I came very close to death, but my life was saved by an unexpected source: one of the locals, a Palestinian resident of Gaza, with whom I am in contact to this day. He was forced to flee Gaza and was granted asylum in the United States.

This book is also the account of Israeli Jews who were forced to fight heroically in order to survive. A story about victory against all odds, the triumph of the few over the many, often compared to the biblical tale of David and Goliath. Of how a small army defeated the powerful armies of five neighbouring Arab countries, who threatened to destroy the young and vulnerable Jewish state. A story of involuntary heroism performed in an extraordinary and unique way, utilizing various sophisticated techniques and calling on extraordinary courage, and with the willingness of young soldiers to sacrifice their lives for the sake of their nation’s tenuous survival. It is the story of a determined people, who succeeded in building from the ashes of the Holocaust one of the best armies in the world, producing sophisticated weaponry and intelligent combat techniques that became the envy of the fighting forces of other nations. It is a story of Jews who were forced to fight back in order to avoid another Holocaust, or a situation in which they could again find themselves scattered around the world, encountering antisemitism and persecution.

I reveal the notoriously tough training regime, which has been described by many as ‘Mission Impossible’. During these nine exhausting months, the selected fighters would be shedding gallons of sweat, breaking limbs, and passing out from the unbearable heat during the gruelling exercises, which were designed to bring the combatant to total physical and mental exhaustion in order to examine his level of endurance. I could not show emotion or shed a tear, but at the end of the nine months’ arduous training, I was very proud to receive the insignia of Most Outstanding Trainee in the unit.

The enrolment into this commando unit starts while still in high school, when teachers are asked by the military authorities to pass on information about pupils who stood out from their classmates in their actions and reactions. Pupils who were seen to be ‘different thinkers’, flexible and improvizational, who would respond to situations while visualizing the whole picture ten steps ahead, and making speedy decisions under pressure. These characteristics were more highly regarded by the military than excellence in maths or physics.

For many years I struggled with the debilitating effects of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, a result of an accumulation of the horrific scenes I had witnessed. I saw massive explosions and burning corpses, and have found myself in near-death situations. My PTSD would manifest itself in my aversion to eating meat grilled on a barbecue, as this reminded me of the sickening smell of burning bodies. I will describe the process I went through to heal myself without medication, in the hope this can help others who suffer from all kinds of anxiety to try to heal themselves, or at least reduce and minimize attacks and have the ability to control them.

A taste from the book:

In the spring of 1990, my company was tasked to infiltrate a small village in Lebanon and blow up a two-storey house that served as the headquarters and training base of the Palestinian Fatah terrorist organization. As we approached the target, the terrorists inside the house started firing at us from the windows. My entire company, with its three platoons, immediately split into three teams. One began attacking the house from its west side, the second flanked the back of the house from its east side, while my team fought in front of the house, targeting the bunker and its trenches from where several other terrorists were also firing at us. Our intention was to get inside the trenches, clear them, and then take over the bunker situated behind them. Meanwhile, the two other platoons would take over the house. As we approached the trenches, the terrorists inside intensified their fire at us. The bullets whistled by and threatened anything in their path; they did not care what type of material they penetrated, whether it was a human body or a concrete wall. Grenades were flying through the air. We lay on the ground and waited for the terrorists to use up all their supply of grenades. When that did not happen, our commander shouted an order, and we all, around 14 fighters, jumped down into the trench, spraying it with our automatic rifles. Once inside, we moved between its narrow sides in one column, with only the fighter at the head of the column being able to shoot forward. If he ran out of ammunition or got hit, he would sit down and cling to the side of the trench to allow the next in line to move forward and continue the shooting, and so on, until the clearance and takeover of the trench was completed.

Despite the intense and stubborn battle that took place inside that trench, we managed to get to the bunker. When we had entered the bunker, we realized it was much larger than it had seemed to us from the outside. It appeared to contain several rooms, something that could complicate the purging and taking over of the entire bunker. We threw grenades into each room and started clearing them one by one. Even though their bare light bulbs were still switched on, there was a thick haze filling each room due to the dust caused by our grenades. This made it very hard to see what was going on around us. We had to find our way by patting the walls with our hands and making sure there were no surprise doors or exits from the room. Within minutes, we had taken over the bunker and the trenches were totally cleared. The battle was over. After a final thorough search, we started making our way out of the bunker towards the helicopter waiting to take us back to our base. On the way, I paused for a moment at the point where the wounded were concentrated. I approached three stretchers on the ground. On the first two lay two of our wounded fighters, but on the third, lay a fighter whose face was covered by a blanket.

This is the most frightening moment in any raid or operation, even more than the fear experienced inside a trench when being shot at and seeing your own certain death. This is the moment you are about to find out which of your friends has been killed, as the faces of those who have been injured are not obscured by a blanket. With a trembling hand, I lifted the blanket from the dead soldier’s face, and immediately a shiver shot down my spine. My knees buckled. It was our revered force commander. A special commander, not only brave and charismatic, but a person with remarkable abilities, a superman who inspired us all. ‘How can this be?’ I shouted. I did not have the strength to cry. I felt like I was choking. ‘How can such an experienced and brilliant professional fighter be killed?’, I muttered to myself. I could not tear my eyes away from the motionless face of my beloved commander who had taught me how to overcome my fears, how to prevail in the most dangerous situations, and had planted the idea in my head that nothing is impossible to achieve.

One of the fighters came over and gently placed the blanket back over the face of our dead commander. He helped me to my feet and whispered that I must proceed to the helicopter as quickly as possible because we needed to vacate the area before more terrorists arrived. I headed towards the helicopter without looking back. I did not want to say goodbye to my commander. I wanted to cry but my eyes were dry. I could not even force myself to take a sip of water, much-needed after our intense battle. I continued walking like a zombie. When I climbed on to the helicopter, I sat down on the floor, huddled in the corner, my rifle between my legs, my head bowed, not saying a word nor looking at anyone. As the helicopter lifted to the sky, the smell of burnt oil and gasoline rose in my nose. An hour later, at the post-battle debriefing, I finally awoke from my shock, as I was required to answer questions coherently and provide clear operational details. It was only during this debriefing session, when everyone involved began to describe the course of the battle and its stages, did we learn that our dead commander had sacrificed his life to save ours in an unusual act of heroism. It happened when we were still dealing with the trenches. Due to the heavy billowing smoke that blurred and restricted our vision, we had not seen that at the top of one of the trenches, a terrorist was hiding behind a machine gun, waiting until we got closer. The only one of our force who had spotted the danger was our courageous dead commander, who immediately run all exposed towards the terrorist, firing at him and paralyzing his actions. By doing so, he not only saved some of us from certain death, but he also made it easier for us to move on towards the bunker. This act of heroism greatly influenced me throughout my military combat service, which was replete with dangerous shooting incidents, where courage and heroism were much needed. However, when we hear or read about an act of heroism, our natural human tendency is to admire, cherish and appreciate it. But when digesting the heavy price paid, we may reconsider these values. This is the conundrum I went through with the heroic death of my revered commander. I sometimes felt schizophrenic. One side of me concentrated on sharpening my fighting abilities, while the other side of me loathed the war, and did not want to hear about acts of heroism during battle. Both these conflicting sides of me were trapped. Neither of them could choose a getaway option because I was in the midst of my compulsory military service.

The foundation of heroism is not just courage. It is more the readiness to sacrifice oneself to save others, a willingness that is the definition of the protagonist. Heroism may be manifested in different contexts, both in unique situations and in everyday ones, and is witnessed in many different forms: physical and spiritual, military, civil, national or social heroism. When I shot a terrorist at such close range that I could see the nicotine stains on his teeth, in doing so, I was able to save two of my company soldiers, but I still do not think I acted heroically. Compared to my commander’s act of heroism, during which he saved others, I did not feel I was carrying out this act to save others. I was actually saving myself first. I wanted to survive the situation that was forced on me. I was not happy to kill. Killing is wrong and inhuman. But there are situations where you are compelled to kill, or you will be killed. And sometimes such situations give rise to an act that in the eyes of others is considered heroism. Although there were several other such incidents during my combat service, I never thought of giving them the title of heroism. I considered them a necessity, something I had to perform in order to survive. Nonetheless I was reluctant to act in such a way. It would only be natural to kill someone who came to kill me, but the more I saw of the enemy with whom I came into combat contact, the more the hatred for him diminished. The closer I was, sometimes at zero range where I could see the colour of the enemy’s eyes, I would feel a pang of compassion for him; I saw in front of me a living human being even though I could end his life in a second. There were times I felt I had been forced into taking part in a war I did not choose to be part of. The rationale of war appeared to me absurd, inconceivable, primitive. I felt like an animal in the jungle, and adopted the jungle imperative where only the stronger and faster will prevail. I grew up in wars, in shelters, under bombings and terror attacks. War has become part of my life, thus, I had to be the stronger, the victor, the best animal in that Jungle. But I hated that jungle.

I was part of the best army in the world, and performed things that the average person does not get to do in his lifetime. I felt like a hero when I subdued the enemy in face-to-face combat in bunkers and trenches. I saw death more often than the breakfasts I ate. I did the impossible, the like of which was only seen in James Bond movies. I was involved in many dangerous activities, and daring raids into Lebanon in pursuit of wanted terrorists. I saw massive explosions and burning corpses, and have found myself in near-death situations. For years I couldn’t eat meat grilled on a barbecue, as this reminded me of the sickening smell of burning bodies. I lost 17 friends and 5 members of my family on the battlefields. However, as I grow older, I realised that this glory alternates with bitterness. I hated war. I realized that war is a stupid invention of mankind. War is an old-fashioned and primitive act, a failure of the use of brainpower. There are no winners in wars. In war there is only grief. However, if I have to fight again for my country, I will be prepared to die for her.

I received appreciation and medals during my combat service. I was fulfilling my ambition to avenge the enemy who had ruined my childhood – a childhood that was stolen from me because I had to spend so much of it in bomb shelters, in fear of sirens, and even of thunder, which to us as children sounded like shelling. However, it turns out that as I grow older, those sublime feelings of invulnerability from being in extremely dangerous situations, in some cases spanning a period of years, and the pride in accomplishing the impossible, slowly subside and become blurred by the bitterness lurking behind each story of battle. This is a rancour that never leaves me, sometimes making me lose my appetite before a meal, or not wanting to laugh, dance, or at least look at the world with optimistic eyes. A bitter taste that continues to swirl around my mouth, and slowly penetrates my heart with the true understanding of the consequences of war. This is an understanding that only appears once the time you were involved in dangerous, almost impossible, operations is well behind you. Only when you have reached the age of wisdom after the age of 40 do you realize that any war, except a purely defensive one, is the dumbest invention of mankind of all time. War is an old-fashioned and primitive act. It is an act of violence and brute force, the opposite principle of social norms of the progressive enlightened world. It is a failure of the use of brainpower.

In spite of the acknowledgement, appreciation, and the number of medals I received during my 28 years of combat service in an elite commando unit, and having the privilege of spending those years among the best fighters, in the best army in the world, I hated war. Even with the exhilaration of participating in dangerous operations in the depths of hostile enemy territory, operations resembling those seen in gripping Hollywood movies, and some which included face-to-face fighting with my bare hands, I still hated war. I also hated its victories. ‘There are no winners in war’, I once shouted at our Minister of Defense then Mr. Shimon Peres who had come to deliver a eulogy at the funeral of a soldier from my platoon, as he announced his promise to continue fighting the enemy until total victory was ours. Despite the numerous victories the army I served in achieved, I never thought of winning a war as a victory. I saw only funerals, pain, tears, suffering, grief and sorrow. War does not lead to any solution. No one has ever ultimately won any war.

It became more difficult over the years when I realized that the war was not against the millions of Arabs around us, something I was so sure about when I was younger. I came to realize that our war was against a limited minority of those Muslims and Arabs. I learned that most Muslims were decent people, not eager for war, and apart from their leaders and the extremists among them, they did not entertain the messianic idea of exterminating the Jews. On the contrary, many of them greatly valued the Jews and saw them as a model for success. Even their Prophet Muhammad preached about embracing the Jews and not harming them. This is written in the Qur’an. After all, Muhammad, while fleeing from his persecutors who sought to harm him, found refuge with Jewish tribes in Saudi Arabia. From them he learned some of the important principles about the Jewish religion, and drew on these for inspiration when drafting the first Qur’anic writings. This insight has caused me many dilemmas on the battlefield, or in the pursuit of wanted terrorists. Each time, the harsh images of those innocent civilians who were caught in the fire against their will echoed in my mind. The last thing we wanted was to hurt these good Muslims, who made up the majority. Those we fought were the extremist groups of terrorists, and those who sent them on their deadly missions. These made up less than one percent of all Muslims in the Middle East.’

Child under war

On a fiercely stormy night in the winter, with bursts of thunder and flashes of lightning getting ever closer in succession, my mother came to the room where my two brothers and I were sleeping in the large double bed shared by the three of us boys. My mother wished to make sure that the window in our room was tightly closed, and that none of us would be scared by the deafening noise of the thunder. I was three years old, and my two brothers were five and seven. As she entered the room, my mother was horrified to discover that our bed was empty. She was overcome by panic, not knowing what to think. She woke up my father who was fast asleep. ‘The children are gone!’ she screamed and started to wail in fear. My dad jumped from the bed and searched the entire house, including the backyard, while reassuring my mom who continued to cry and whine. Only after many minutes of tension and panic, did they find out what had happened to their small children during that stormy night. It turned out that their usually disciplined children, who had been woken up by the thunder, had jumped out of their beds, and without waiting for instruction, raced down to the bomb shelter about 30 kms down the road, believing the thunderous noise was yet another bombardment from Gaza.

To us as children, our run down to the bomb shelter was no more than our daily routine, and we were sure our reaction was a necessary and normal act. However, to the adults around us, it was a disturbing incident that symbolized the horrific reality we were living in, the madness of growing up under the shadow of war.

I was born under fire and brought up under constant war. Much of my childhood was spent in fear and running in and out of shelters. I did not choose to be born into such a reality. I did not choose to be born at all. But from the moment I was born, almost every day I felt that this was the day I could die or be severely injured. I never remember experiencing a feeling of safety since my earliest days of memories. I was born and raised not far from the border of the Gaza Strip, which in those days was under Egyptian rule. The Egyptians, in coalition with other Arab states, had declared an eternal war on Israel until the day of its destruction. During the 1950s, 60s and 70s everyone who lived near Israel’s southern border with Egypt suffered from incessant shelling and terrorist attacks, including those occasions when we were attacked by terrorists armed with large knives, who were insurgents from nearby Gaza. One incident I remember very well. I was only 5 years old but to this day, I recall all the details and even the face of the terrorist who tried to attack me and my family inside our own home. As a result, my entire childhood was swathed in fear and anxiety. The dread of the wailing of a siren, the long periods of sitting in a bomb shelter, the frightening noise of explosions, the panic I felt every time I heard a plane passing overhead, the fear of the violent infiltrators who used to come to us from Gaza with guns or deadly knives in their hands, all contributed to my difficulties in concentrating at school by day and my bedwetting by night. These fears and traumas eventually led me to avenge my destroyed childhood by joining a commando unit to fight my country’s enemies as soon as I became an adult. However, even though I joined my country’s war effort with great motivation, I was reluctant to take part in it as I detested the term ‘war’.

After my military service I suffered from severe post-traumatic stress (PTSD). It would manifest itself in my aversion to eating meat grilled on a barbecue as this reminded me of the sickening smell of burning bodies I had encountered on the battlefield. I did not report my trauma as I was too ashamed to get medical treatment and become categorized as mentally ill, when everything in my personal military file had been noted as excellent. It was only after six years that I decided to expose my personal wound and agreed to take the medication prescribed by a caring physician at the local clinic. I still insisted on withholding my trauma from the military authorities, even though I could qualify for free treatment from them. But these drugs did not heal me, they only eased the symptoms of my illness, and there was a serious downside to the medication. For many years, I refused any invitation to speak publicly, either individually or on a panel, or be interviewed about my experiences for any TV documentaries. I was also asked by a production company to act as a script advisor on a war movie but had to decline as I knew it would be too emotionally difficult for me and might trigger distressing memories that would return to haunt me. Finally, in 2010, after several sessions with an eminent psychotherapist who advised me to start speaking and writing about my combat experiences, I started to give lectures about the history of the Middle East conflicts, mainly the Israeli-Palestinian one, and shared with my audiences stories from my own experiences. In 2017, I decided to stop using the drugs, which had been causing me anxiety and even some behavioural disorder. I researched about alternative therapies online and started applying them on myself. For the first year I had difficulties in persevering in this because I didn’t see any noticeable results. Nonetheless, I refused to give up. Today, I can reveal that my tenacity and perseverance has paid off. For the past few years, I have not suffered from any of the frightening phenomena that accompanied my life for so many years. I realized I had healed myself from PTSD without the use of drugs.

During war, soldiers and commanders often encounter another battle, one that takes place inside the combatant’s mind and which is often termed a moral dilemma. In telling my story, I will relay situations involving moral dilemmas that I have personally experienced, such as:

Shooting at children – During the Lebanon War, we encountered a disturbing phenomenon where Lebanese children were facing us with Russian RPG missiles (rocket propelled grenades) in their hands. To the world’s media they became known as ‘the RPG children of south Lebanon’. We had to make split-second decisions about whether to shoot at them or run away. Our dilemma was two-fold, firstly whether to shoot at children or turn and flee, and secondly, that commando units are trained to deal with danger, never to run from it.

Checkpoints – The decision for a soldier whether to allow a child or a pregnant woman to pass through an Israeli checkpoint for critical hospital treatment carries a high level of risk. The soldier assessing the individual situation is aware that there have been many deadly incidents previously in which an innocent looking woman or child had blown themselves up with explosives hidden on their body, taking along with them the lives of both soldiers and civilians.

Saving the life of the enemy – During a hard-fought battle against hundreds of terrorists, who were protected by hiding within densely packed terrain, I voluntarily carried a wounded terrorist on my back to get him medical treatment. He was the very same enemy soldier who, just a few minutes earlier, had been trying to kill me. It was not an easy thing to do. I remember pointing my gun at his head, wanting very much to end his life, but after a few seconds, I controlled myself and let my vengeance and fury subside. I chose to save his life.

Methods of training and operating

Apart from being taught skills such as navigation, climbing and administering first aid under fire, our physical training exercises included a daunting 190 km trek on foot over dusty and rocky roads, facing steep slopes and areas of ground thick with mud. Just two days after this is completed, we are ordered on a further 110 km trek carrying a stretcher with a ‘wounded’ soldier on it. Other training exercises involved carrying weapons, ammunition and personal equipment weighing nearly 80% of our body weight, while climbing a 14 km uphill mountain path, scaling a mountain while shooting at marked targets, and parachuting in the darkness towards an unlit and unmarked destination, while maintaining constant and accurate gunfire. During our navigation course, commanders demanded that we should learn the art of navigation at night in enemy territory, in real time, exposing us to the dangers of a surprise encounter with the enemy. As with parachuting, this was an extreme method of testing courage and giving the soldiers an authentic experience. Although most of us loved the excitement of such a crazy practice, some seniors considered it as unprecedented in training, and it was actually abolished in 1968 due to its high risks.

Another ‘highlight’ was a week spent enduring hunger, living in a field where we had to forage for our own food each day. This involves eating grass, rhizomes, insects and reptiles, items that you would not find at the supermarket in your daily life. This is a survival course aimed at hardening us to face the harshest of conditions, including persistent hunger, long hours of thirst, very high temperatures in summer and, in winter, unbearable cold. These exercises bring the combatant to total physical and mental exhaustion in order to examine his level of endurance.

In collaboration with an undercover unit, we were sent to a genuinely hostile location, and were shown how, as a solo fighter, we could find way out should we find ourselves trapped in an enemy civilian crowd, or left alone in the field surrounded by enemy soldiers. The principle was to show us how to use our intellect and character skills more than the weapons in our hands.

Techniques we learnt to use within a built-up area were the ‘cold entry’ and ‘hot entry’, two different methods of storming and taking over a house, or any structure that has civilians inside and is built in a crowdy build-up area. For a cold entry, we were trained in handling dangerous situations with our bare hands, without firing a single bullet so as to minimize casualties among the hostages or innocent neighbours. This is done after silently heading towards the target and taking it over in the blink of an eye. An example of where this method is used is for breaking into a house to rescue civilians being held hostage by a single armed terrorist, whether armed with a gun or knife. The decision as to the type of action in this situation would depend to a large extent on the information at our disposal regarding the type of weapon the terrorist possesses. If he is holding a knife, we would choose to first attack without firing and neutralize him by various other means. If he is holding a rifle, we would still first try an assault without firing, or with our bare hands, so as not to injure any hostages. If this fails, then we would have no choice but to shoot the terrorist, but would use the skill of our snipers and our own ability to shoot with great precision.

This cold entry method is also designed for entering a house to capture a wanted terrorist, even if hostages are not involved. Such an operation requires us having excellent intelligence about the location, usually supplied by the undercover ‘Mista’arvim’ unit, who will have been familiarizing themselves in the area by roaming around the streets and gathering information. To execute this kind of operation, the element of surprise is the key, using deceptions and tricks so as not to be spotted before arriving at the location, as any small mistake could scupper the mission and put a commando’s life in danger. The fighters are trained to memorize all details, names, colours and shapes, and be fully aware of any minor change in the area to minimize any chance of being spotted. If our soldiers are attacked, then a stand-by back-up unit would arrive quickly on the scene and storm the area, escalating the mission into a larger-scale combat situation, something that commando fighters strive to avoid.

I have tried as much as possible to give my writing an anti-heroic, peace-promoting, and humane touch. I have also omitted some situations in battles and operations in which I know I acted courageously. My intention here is to tell a story based on real events, while emphasizing the events themselves and not their participants. I did not like the things I was forced to do or experienced in the many operations I took part in, even though many of them brought with them great achievements, both nationally and personally.

As I got older, I came to hate everything to do with politics and war. I found myself going to talk to those in the enemy camp to see how a solution could be found for coexistence. I risked my life travelling to Gaza and the West Bank to spend time with Palestinians in order to hear their views. This led me to a firm conclusion, and it is that Palestinians want peace and need Israel, but the extremist terrorist organizations, acting in the perpetuation of their own interests, will not allow it. From these conversations, I discovered to my amazement that the Palestinian people for the most part no longer want to be living under war, but that they are locked inside the violent struggle imposed on them by the terrorist organizations who continue to brainwash them. Hence my sympathy towards the Palestinians, even though I fought against them for much of my life. They were my enemy, but over the years, I learnt that their misery has increased only because they are constantly in fear of their Hamas leaders, not of the Israeli tanks. The majority of Palestinians wish to live alongside Israel, who throughout the years of occupation provided them with work and services such as electricity, water and free medical treatment. They see in Israel a solid democratic and free state, as well as a technologically and scientifically advanced country in which a profitable future could be planned and built.

Although I sought revenge and fought those whom I blamed for ruining my childhood, I avoided harming Palestinian civilians and even risked my life many times to do so. I also saved many of them from being harmed by the terrorists who showed no concern for their safety. To them, Palestinian civilians were just cannon fodder. To me, these Palestinians were as human as all human beings, and they deserved the right to live.